Primal Male Impulses: Evolutionary and Psychological Perspectives

Across cultures and history, men have been driven by primal impulses often summarized as the urge to fight, feast, and procreate. Modern research in evolutionary psychology suggests these core drives are rooted in biology and have changed little over millennia. Men are universally more prone to physical aggression than women, a pattern seen in every society – men commit and are victims of the vast majority of violent acts and homicides.

This sex difference in aggression appears hard-wired; it persists across varied cultures and eras, indicating an evolutionary function rather than mere socialization. Biologists theorize that male aggression historically conferred advantages in competition for resources and mates. As one scholar put it, it would make no sense for natural selection to give men greater muscle mass “but not the psychological machinery to operate it”. In other words, if evolution made men physically equipped to fight, it likely also instilled the desire to fight, paralleling how having teeth and a stomach comes with hunger.

Check here to read more posts on Gender Equality.

Equally ingrained is the male sexual drive. Large-scale analyses confirm that men, on average, report a considerably stronger libido than women. In a review of over 200 studies worldwide, researchers found men think about sex more often, fantasize more, and have higher desire across all ages and cultures. This finding was “consistent across countries, age groups, ethnicities or sexual orientations,” suggesting a near-universal psychological pattern. Evolutionary theory again offers an explanation: because one man can father many offspring in a short time, males historically benefited from seeking multiple mating opportunities, whereas females (who invest more in each offspring) evolved to be choosier. The result is an innate male impulse to “sow seed” widely, driving men’s strong and sometimes unruly sexual urges.

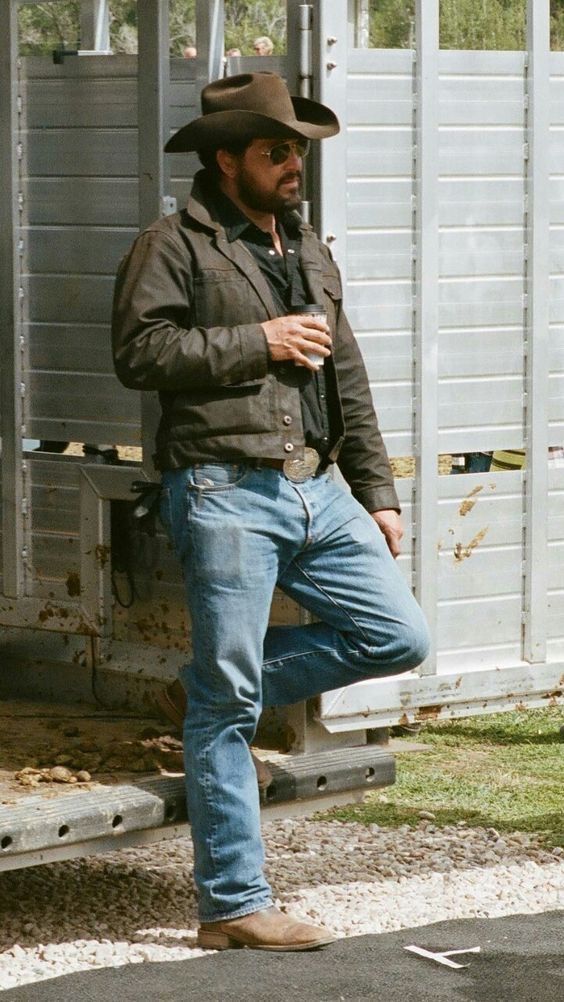

A third component of the masculine triad, symbolized here as “feast,” can be interpreted as the impulse toward consumption, indulgence, and revelry. Anthropologists note that men’s social activities often centred on sharing food and drink as a way to bond and display status. For example, in hunter-gatherer contexts, a successful hunt (born of aggression and skill) would lead to communal feasting – rewarding the hunters with calories and prestige. Biologically, men have higher caloric needs on average, and culturally, male gatherings often celebrate eating and drinking in excess (think of ale-drinking feasts or modern tailgate parties). While less studied than aggression or sex, the feasting impulse aligns with an evolutionary logic: a male who can acquire and consume plentiful resources signals strength and status, which historically could attract mates. In short, the drive to dominate (fight), to indulge (feast), and to reproduce (fuck) can be viewed as foundational aspects of male psychology shaped by millennia of evolution and competition.

Modern psychology echoes these points. The concept of the “young male syndrome” describes how adolescent and young adult men are especially prone to risk-taking, showing off, and aggressive behaviour during their peak mating years. Studies find that young men (late teens through 20s) take more risks – from reckless driving to daring stunts – largely “during periods of peak reproductive competition” as a way to display prowess and impress potential partners. This manifests the ancient logic of male competition in today’s world. As evolutionary anthropologist Cyril Grueter explains, risk-taking can be seen as “a means for young men to display their qualities and skills… which could make them more attractive to women.” In essence, the male psyche is still tuned to fight for status, feast to show resources, and seek sex for reproduction, even if the way these drives are expressed has evolved with society.

Fight, Feast and Fuck: A Feminist Manifesto on Toxic Masculinity

Masculinity in Warrior and Aristocratic Cultures

Historically, many societies celebrated and institutionalized these male impulses through the roles of warriors, knights, and nobility. In medieval Europe, for instance, the ideal nobleman’s life was practically an embodiment of fight, feast, and procreate. The aristocracy was a warrior class – prowess in battle was the ultimate mark of manhood. Knights earned honour and renown through combat, whether in real wars or in ritualized tournaments. Medieval literature and codes of chivalry reveal that a knight was expected to be ferocious in combat yet civilized in peace, encapsulated by the saying “a lion in the field and a lamb in the hall.” A chivalric hero was to unite violence and meekness in proper measure. In the field, he fought boldly; in the banquet hall, he was courteous and gentle.

This ideal acknowledges that aggression was a virtue when used for honourable purposes (defending one’s lord or land), and it had to be tempered by discipline and mercy off the battlefield. The code of chivalry, sworn by knights of the Round Table, for example, forbid wanton cruelty or murder, but it still valorised martial strength. In practice, many medieval knights revelled in violence. The 12th-century knight and troubadour Bertran de Born wrote poetry delighting in war’s chaos; he listed among the pleasures of spring not just flowers and birdsong but “knights splitting heads and hacking arms” and “corpses in ditches.” His relish for war was unapologetic, “celebrating violence” for its own sake. Such accounts show that medieval masculinity openly honoured the warrior ethos – battle wasn’t just a necessary evil, it was often a source of pride and even joy for the men who excelled at it.

Alongside fighting, feasting and indulgence were integral to aristocratic masculinity. Great feasts symbolized a nobleman’s power and success. In the Middle Ages, only the elite could afford lavish banquets, so the ability to “feast” extravagantly became a marker of status and manhood. Historical records of medieval courts describe tables overflowing with game meat, bread, and spiced wine, enjoyed in long revelry. “The eating habits of the nobility in the Middle Ages were a reflection of wealth, power and social status,” featuring “indulgence, extravagance and sophisticated table manners.” Kings and dukes would host days-long feasts after victories or on holy days, where gluttony was practically expected. Certain foods like venison were coveted trophies of the hunt (tying feasting back to fighting skill), and consuming them in quantity proved one’s dominance over nature and fortune. For example, King Henry VIII of England was infamous for his prodigious appetite. His diet consisted of “huge quantities of meat, fine white bread, [and] sweet pastries”, with very few vegetables – a display of opulence that his courtiers dared not question. Despite the obvious health consequences (his later suits of armour had to be enlarged for his growing girth), Henry’s gluttony was indulged as a prerogative of his kingship. To be a powerful man was, in part, to eat and drink to excess and not be challenged for it.

The sexual aspect of historical masculinity was equally pronounced, though often double-edged. Medieval and ancient cultures generally granted men far more leeway in sexual behaviour than women. Noblemen were expected to sire heirs – virility was crucial to continue the family line – and having a mistress or two was not unusual for kings and high lords. In fact, sexual conquest could enhance a man’s reputation. The very term “virile” (from the Latin vir, man) connotes both manly strength and sexual potency. Aristocratic men frequently married for political alliance but maintained lovers for passion, a practice tacitly accepted as long as it was discreet. Even the chivalric romances, while idealizing courtly love as pure and ennobling, often revolve around a knight proving himself worthy of a lady’s affection – implying masculine identity was tied to winning female admiration. Furthermore, many warrior cultures linked sex and victory more directly. In some accounts of conquest, victorious soldiers were “rewarded” with the enemy’s women (a tragic reality of war). The idea of “to the victors go the spoils” included women as spoils in patriarchal contexts. More metaphorically, Norse mythology imagined Valhalla (the warrior’s heaven) as a place where fallen heroes would fight all day, then feast and enjoy mead served by maidens at night – an afterlife of eternal fighting, feasting, and presumably fornicating. Such stories reinforced the notion that indulging these instincts was a rightful reward for masculine excellence.

In summary, historical models of manhood, from medieval knights to Viking raiders, embraced men as fighters, consumers of plenty, and sexual actors. These traits were not viewed as shameful; on the contrary, they were honoured and regulated. A nobleman was expected to excel at combat, to be generous in celebration (hosting feasts, dispensing largesse), and to be virile, fathering children and satisfying his desires. While moral codes (like chivalry or religion) sought to channel and civilize these drives – encouraging mercy in victory, moderation in indulgence, or fidelity in marriage – the core impulses themselves were never denied. A medieval man’s honour and identity were built on harnessing his aggressive and appetitive instincts in socially approved ways. Society needed his warrior spirit for defence, his feasts for communal bonding, and his procreation for continuity. In these traditional settings, the motto “fight, feast, fuck” could almost be taken as the nobleman’s mission statement – albeit phrased in the elevated language of honour, hospitality, and lineage.

Modern Repression of Masculine Instincts

As civilization advanced and norms changed, many of these once-valued male traits began to be reined in, reinterpreted, or vilified. Over the last few centuries – accelerating dramatically in recent decades – society has placed new constraints on the raw impulses of men. The reasons range from maintaining public order to pursuing greater gender equality and reducing violence. But the result is that the traditional outlets for male aggression and indulgence have narrowed, and behaviours once seen as “manly” may now be labelled as problematic or “toxic.”

Physical aggression, for example, is no longer something the average man can express freely without consequence. In medieval times, a knight could respond to an insult with a duel; a Viking could simply brawl or go raiding. Today, violence outside of very specific contexts (like consensual sports or legitimate self-defence) is illegal and socially condemned. Men still feel anger or aggressive urges as ever, but society expects them to restrain themselves. Starting in the 19th century, with the spread of law enforcement and the decline of honour duelling, it became less acceptable for men to settle disputes with fists or swords. This is of course a positive development for public safety – we no longer tolerate open brawling in the streets – but it also means one classic masculine release valve has been shut off. Young men full of testosterone are told to “use your words, not your fists,” a far cry from the days when “might made right.”

In the realm of sexuality, modern norms have tightened around men’s behaviour as well. Traditional patriarchal cultures often winked at or even praised a man with multiple lovers (the “stag” archetype of virility). Contemporary society, aiming for sexual equality, condemns open philandering or any non-consensual pursuit. We enforce strict laws and norms against sexual harassment and assault – again, a very necessary protection – but it frames uncontrolled male sexual aggression as a grave sin (rightly so). Even consensual promiscuity by men can draw social criticism in an era where fidelity and respect for partners are emphasized. The old double-standard (“boys will be boys” while women were shamed) is fading: now “player” behaviour is often critiqued as exploiting women or reflecting insecurity. Men’s sexual advances are expected to be respectful and welcome, not aggressive or entitled. Pornography and media that objectify women face backlash for encouraging predatory attitudes. Overall, the male sex drive, once almost celebrated as the driving force of courtship and conquest, is under careful scrutiny – with men admonished to temper their “fuck” instinct to ensure it’s respectful and consensual.

Even the feasting (indulgence) impulse has been moderated by modern values. Qualities like moderation, health consciousness, and politeness now curb the open gluttony or drunkenness that might have been acceptable for a medieval baron. A man who overeats or drinks to excess today might be viewed as lacking self-control or having a problem, rather than as a jovial leader of the community. Public displays of indulgence (drunken bar fights, rowdy “boys’ nights” antics) are often stigmatized as immature or uncouth. In many professional and social settings, men are expected to show restraint – too much eating or drinking is seen as undisciplined. The seven deadly sins of Christian tradition included gluttony and lust, of course, and those moral codes always cautioned men against overindulgence. But modern secular culture adds practical critiques: indulgent men might be called “man-children” or seen as failing to adapt to a civilized, egalitarian society.

A key concept that has emerged in recent years is “toxic masculinity.” This term, popularized in media and academia, captures the idea that certain traditional male behaviours actually harm society and men themselves. Toxic masculinity refers to those aspects of dominant masculinity that are socially destructive, such as misogyny, homophobia, and violent domination. For example, a man proving his manhood through bullying or aggression, or suppressing all emotional vulnerability to appear “tough,” would be exhibiting toxic masculine norms. The saying “boys will be boys” is often cited as an excuse that historically normalized male aggression and misbehaviour. Modern critiques push back against that, arguing that we should not excuse violence or aggression as just male nature, because doing so perpetuates harm (from bullying and domestic abuse to mass shootings). Instead, society increasingly polices masculine behaviour: encouraging boys and men to be empathetic, to seek consent, to manage anger without violence, and to reject sexist or homophobic attitudes.

To illustrate, consider how emotional expression in men has been reframed. Traditional norms told men to “man up,” stay stoic, and never show weakness. While meant to cultivate resilience, this can cross into emotional repression – teaching men to bottle up sadness or fear. Research now shows that extreme self-reliance and emotion-suppression correlates with serious mental health issues in men, including higher rates of depression, stress, and substance abuse. Thus, what was once a prized stoicism is recast as a silent killer, contributing to men’s disproportionately high suicide rates. The American Psychological Association in 2019 even issued guidelines warning that “traditional masculinity ideology” – marked by competitiveness, aggression, and emotional suppression – can be harmful to boys and men, leading to problems in mental and physical health. Although this stance was controversial, it reflects a growing consensus in psychology: some longstanding male norms need to be softened for men’s own good.

In sum, modern society has in many ways put the brakes on men’s raw impulses. Overt aggression is punished, unchecked sexual pursuit is stigmatized or criminalized, and even carefree indulgence is frowned upon as unhealthy or immature. The “fight, feast, fuck” mantra of old doesn’t sit easily in a world of HR departments, consent workshops, and health diets. Many of the rough edges of masculinity have been filed down by legal, social, and economic changes. This is not without good reason – it has made the world safer and more equal. Yet, it sets up a profound tension: male nature vs. modern norms. The core drives remain – men still feel the itch to compete, to revel, to pursue sexual excitement – but they now navigate a culture that often tells them these urges are bad or dangerous. This clash between evolutionary legacy and contemporary values is the crux of many debates about masculinity today.

…modern society had made men passive, aimless, or rageful by stripping away ancient rites of passage and positive male role models.

Mythopoetic Men’s Movement

Contemporary Masculinity: From Sports to Social Media

Despite society’s constraints, the primal impulses of men continue to find expression in modern cultural outlets – sometimes in sublimated, socially acceptable forms, and other times in controversial subcultures. One of the most prominent arenas where the fight/feast/sex instincts play out today is sports culture. Sports are essentially ritualized combat, and they serve as a safe proxy for war in which men can compete fiercely without actual bloodshed (usually). Biologically, men are drawn to sports partly because athletic competition mimics the movements and skills of primitive hunting and warfare: chasing, tackling, aiming projectiles, strategizing in teams. A scientific study noted that men enjoy watching and playing sports as it engages the same neural and physical circuits that once helped their ancestors pursue prey or battle rivals. In spectating, men also get to vicariously experience combat and analyse dominance hierarchies – observing which athletes triumph and why. This can have an almost evolutionary logic; one researcher likened watching sports to evaluating potential allies and enemies, as ancient humans might have done, and to learning by observation which behaviours lead to victory.

Sports also encapsulate the feast and sex elements of the male triad. Successful athletes often enjoy great wealth and status, which they (and their fans) celebrate in feasts of a sort – victory parties, champagne spraying, lavish dinners. Fans too indulge: the ritual of the tailgate party before a football game, with abundant grilled meat and beer, is practically a modern tribe’s feast before battle. It’s socially acceptable for men who might be buttoned-down professionals on weekdays to paint their faces, go shirtless in winter, scream war chants, and devour lots of food and drink on game day – all an outlet for tribal aggression and indulgence. The link to sex is also present: star athletes often become sex symbols with increased access to willing partners (the trope of athletes with many “groupies” or being idolized by women).

Indeed, some scholars describe sports as a “mating ritual” for men. Achieving in sports can increase a man’s attractiveness and his “mating pool,” as one article put it. High status in the sports hierarchy can translate into more sexual opportunities, which is a direct echo of evolutionary rewards. Men themselves often correlate their status with sexual success, so winning a championship or even just being a die-hard fan of a winning team can boost confidence in courting. As sociology professor Douglas Hartmann observed, “The American male’s obsession with sports seems to suggest that the love affair is a natural expression of masculinity.” It centres on competition, physical prowess, and pride – all key ingredients of traditional manhood.

Beyond sports, popular culture and media provide other outlets. Violent video games and action movies, for example, allow millions of men (and women, though men are the primary demographic) to engage in virtual fighting and dominance. The popularity of franchises like Call of Duty or John Wick speaks to the thrill many men get from simulated combat and heroics – a modern, harmless channel for the warrior instinct. Comedy and advertising also tap into these themes: consider the enduring cliche of the “hungry man” satisfied by a big steak or the humorous trope that a man’s simple needs are food and sex. One tongue-in-cheek slogan circulating online advises women that “the best way to satisfy a man is [to] empty his balls and fill his stomach.” (Crude as it is, the joke resonates because it feels true to many – reflecting the idea that a man who is well-fed and sexually sated will be content.) Even in dating advice or marriage jokes, we see this echo of the feast and fuck formula: feed him, please him, and he’ll stick around. It’s a pop-culture distillation of presumed male basics.

In recent years, public figures and influencers have emerged as outspoken proponents of embracing traditional masculine impulses. Perhaps the most notorious is Andrew Tate, a former kickboxing champion turned social media personality, who preaches an unapologetic brand of hyper-masculinity. Tate’s messaging glorifies male dominance, wealth, and sexual conquest – in essence, telling men to fight (be tough and combative), feast (get rich and enjoy luxuries), and fuck (sleep with many women) as markers of success. He often laments that modern society has made men weak and that feminism is to blame for “dethroning” men from their natural place. He brazenly urges a return to a worldview where men lead and take what they want.

For instance, Tate has suggested that a man should control his woman and that infidelity by men is acceptable (while by women is not) – reflecting an extreme indulgence of the old double standard. Though widely criticized as misogynistic, his ideas have gained a huge following among young men online. The appeal comes largely from his framing: he positions himself as a defender of masculinity under siege, claiming that society unfairly vilifies men’s natural desires, and that men should reclaim pride in being men. Tate’s popularity indicates a backlash to the modern suppression of male urges – he offers an outlet (albeit a toxic one) for men to feel powerful, aggressive, and entitled to pleasure without apology.

In a somewhat different vein, clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson has also become a prominent voice on modern masculinity. Peterson doesn’t advocate promiscuous indulgence like Tate, but he does argue that strength and aggression are not inherently evil – if anything, they’re necessary. One of Peterson’s well-known maxims is that a man should be capable of being dangerous, but responsibly contain that capacity. “You should be a monster, an absolute monster, and then you should learn how to control it,” Peterson advises, invoking an old proverb: “It’s better to be a warrior in a garden than a gardener in a war”.

…modern society has made men weak and feminism is to blame for “dethroning” men from their natural place.

Andrew Tate

What he means is that harmlessness is not virtue; a good man is one who could fight ferociously but chooses to be peaceful. This perspective directly defends the “fight” instinct as something to be integrated, not eliminated. Peterson also frequently criticizes messages that demean men. He voices concern that young men are growing up hearing nothing but scorn for “patriarchy” and “toxic masculinity,” and thus feel lost or demonized for simply being male. In his book and lectures, Peterson encourages men to embrace responsibility, competition, and risk-taking in constructive ways (start a family, build a career, face challenges head-on) rather than withdrawing. He often extols traditionally male-coded virtues like courage, industriousness, and protectiveness. While he supports women’s equality, he warns against any ideology that pathologizes masculinity itself. Peterson’s huge following (millions have read his 12 Rules for Life or watched his talks) shows that many men are seeking guidance on how to be proudly masculine in a world that sometimes only tells them what not to be.

Even in everyday popular culture, the enduring male archetype of the “provider-protector” still finds love. Superhero movies (the most popular film genre globally) are essentially modern myths of men with extraordinary fighting abilities who protect others – a power fantasy that appeals strongly to male audiences. The celebration of soldiers and first responders in culture similarly taps into the notion that to be a man is to protect and if necessary fight. On the lighter side, social media trends like the chuckle over men’s simple needs (a cold beer, a big meal, and some loving affection) show a recognition – sometimes ironic, sometimes affectionate – that the basic male template hasn’t vanished. For example, a viral post might joke: “Ladies, if your man is grumpy, feed him and love on him. Men are basically golden retrievers with wallets.” It’s comedic, but it echoes the same “feast and fuck” formula in kinder terms.

Thus, contemporary culture is ambivalent: on one hand, it restricts and critiques raw masculinity; on the other hand, it channels and indulges it through sports, entertainment, and charismatic figures who give voice to male frustrations. The popularity of figures like Tate and Peterson, or the billions spent on sports and action media, indicate that men still crave outlets for their ancestral impulses. When mainstream society disallows something (e.g. casual aggression or unabashed male dominance), it tends to reappear in subcultural ways – sometimes positive (competitive sports, vigorous debate, consensual fantasy play) and sometimes negative (online misogyny, violent extremist groups). The current landscape is essentially a negotiation for men: how to reconcile their deep-seated drives with the expectations of a changed world. This has led to a heated debate about masculinity’s place today, with strong voices on both sides.

Feminist and Critical Perspectives on Masculinity

Not everyone agrees that the “fight, feast, fuck” essence of manhood should be valorised or even accepted. Feminist thinkers and other critics argue that clinging to these primal impulses has a dark side – it underpins patriarchy and harms both women and men. From a feminist perspective, what some call men’s “unchanged nature” is often socially constructed behaviour that can (and should) be changed to create a more just society. They contend that violence, sexual entitlement, and domination have been tools of male supremacy, not inevitabilities. Therefore, much of the modern repression of traditional masculinity isn’t seen as an attack on men, but rather as progress toward equality and safety.

One key critique is that the notion “boys will be boys” has long been used to excuse harmful behaviours. For instance, aggressive bullying or fights in school were sometimes shrugged off as just what boys do. Feminist analysis says this leniency enabled a culture where male aggression is normalized, leading to outcomes like domestic violence, street harassment, and even militarism. By labelling these behaviours as “toxic masculinity,” society is finally calling them out as neither benign nor inherent, but as choices shaped by culture. The term toxic masculinity itself, when properly understood, doesn’t condemn men for being male; it criticizes specific harmful behaviours and norms that boys are socialized into. These include the idea that real men must be dominant, callous, and never emotionally vulnerable. Such norms have obvious negative effects: they can fuel misogyny (viewing women as conquests or inferiors), homophobia (hating anything seen as unmanly), and acceptance of violence as an outlet. Critics point to phenomena like rape culture – where male sexual aggression is downplayed – as the extreme outcome of unrestrained “male nature.” From this view, society evolving beyond “fight, feast, fuck” is a good thing: it means less violence, less sexual coercion, more sharing of resources, and more emotional freedom for everyone.

Feminist scholars also question the idea that male traits are fixed by biology. They highlight how different cultures have had very different models of masculinity, implying flexibility. For example, not all societies glorified warrior violence to the same degree; some indigenous cultures valued cooperation and had strict rules against intra-group violence, even among men. If male aggression were purely innate, such variations wouldn’t exist. Thus, they argue gender is largely a social construct – boys learn to be tough, girls learn to be gentle, etc., and these can be changed. The concept of hegemonic masculinity in sociology describes how a certain aggressive, heterosexual, stoic model of manhood became dominant in a given society, marginalizing other ways to be a man. But alternative masculinities (e.g. more nurturing, artistic, or egalitarian male roles) have always been around. Feminists encourage broadening the definition of manhood beyond the old triad, to allow men to be caregivers, empathic, and cooperative without shame. In other words, they seek a masculinity not centred on fighting, feeding, and breeding.

Another feminist critique addresses the power imbalance inherent in traditional masculinity. Historically, when men did all the fighting and ruling, women were excluded from power and often suffered under male excesses (from forced marriages to being spoils of war). The feast of noblemen was often on the backs of peasants’ labour, and the sexual indulgence of powerful men often meant exploitation of women without agency. Thus, critics say romanticizing the past ignores how those male impulses unchecked often meant oppression for others. A medieval lord’s freedom to “feast and fuck” was enabled by a system that treated women as property and commoners as expendable. In the modern era, feminists vigilantly oppose figures like Andrew Tate because they see a direct line from his ideas to violence against women. Tate’s rhetoric (that women owe men sex, that men should dominate) is viewed as dangerous instigation of abuse. Sociolinguist Robert Lawson remarked that Tate’s brand of hyper-masculinity is essentially “grotesque misogyny” repackaged as self-help, and it appeals to male insecurities by blaming women. Women’s advocates argue that we must continue to challenge and dismantle these old masculine norms, not defend them, if we want a safer world.

Furthermore, some male allies and psychologists critique the primal-man worldview for hurting men on a personal level. When society expects men to always be strong, unemotional providers, many men who struggle to meet those ideals feel like failures. There’s a growing movement in mental health emphasizing that men need permission to be vulnerable and seek help. The “fight, feast, fuck” model leaves little room for men to be, say, gentle caregivers or to admit they’re depressed or to reject the pursuit of sexual conquest. Feminist author Bell Hooks, in her book The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, argues that patriarchy forces men to “cut off” the emotional parts of themselves, which leads to profound loneliness and anger. Thus, critics maintain that patriarchal masculinity is a cage for men, too, even if men historically were the beneficiaries of the system. They encourage men to break free by redefining masculinity in a healthier, more holistic way.

It’s important to note that not all feminists demonize men’s nature; rather, they seek to distinguish between male energy and male entitlement. For instance, being physically strong or enjoying sexual pleasure is fine – it’s the use of strength to harm or coerce that’s condemned. Some feminist writers actually celebrate positive masculine qualities, especially when decoupled from sexism. The idea is that men can be powerful and gentle; the old archetype of the hero who protects the village can be preserved without the side effect of oppressing the village women.

There’s also a strand of modern feminism that engages with evolutionary psychology, not to excuse bad behaviour, but to better understand it and then channel it constructively. They argue that if men have a predisposition toward aggression, we should ensure societies have healthy outlets (like sports or physical jobs) and strong norms against using it destructively, rather than pretending men and women are the same. In sum, the feminist and critical perspective does acknowledge male instincts but insists they are not static or unchangeable – and that clinging rigidly to them out of nostalgia can impede progress toward a more equitable society.

Toward an Integrated Vision of Masculinity

Between the extremes of “let boys be boys” and “men must change everything about themselves” lies a growing call for a more integrated, empowered vision of masculinity. Many thinkers – including some feminist men, psychologists, and philosophers – argue that the goal should be neither to eradicate traditional male traits nor to indulge them recklessly, but to harness them in positive ways. This integrated approach says: yes, men do have certain innate tendencies (on average) – but instead of repressing these completely, we can channel them toward good ends while also encouraging men to develop new strengths like emotional intelligence and mutual respect.

One inspiration comes from the aforementioned mythopoetic men’s movement of the 1980s/90s (led by figures like poet Robert Bly). Interestingly, this movement originally coined the term “toxic masculinity,” but not to malign masculinity – rather to separate the harmful mask men wear from what they saw as men’s “deep” true masculinity. They delved into myths and archetypes (the King, Warrior, Magician, Lover, etc.) to help modern men reconnect with healthy forms of power. The mythopoetic view was that modern society had made men passive, aimless, or rageful by stripping away ancient rites of passage and positive male role models. Their solution was not to shame men, but to guide men toward mature masculinity – one that includes bravery and strength (the Warrior), but also wisdom, creativity, and love. An integrated masculine ideal, in this sense, might be a man who is protective, not predatory; competitive, but fair; proud, yet humble; strong, and also compassionate. This echoes the chivalric balance from earlier – ferocity and mercy together – updated for our times.

Psychologically, integration means acknowledging the “shadow” impulses (violence, lust, hunger for power) within a man and finding pro-social outlets for them. For example, rather than demonizing male aggression, some suggest we provide structured ways for boys and men to express it: martial arts classes that teach discipline and respect, wilderness programs that satisfy the urge to test oneself against nature, or even competitive team games that build camaraderie. These can satisfy that “fight” drive in a contained, constructive fashion. Similarly, the feasting impulse can be channelled into positive forms of celebration – encouraging men to take joy in cooking, to be hospitable, to savour achievements with friends and family, without veering into destructive excess. The idea is to transform gluttony into generosity: a man’s desire for abundance can become the impulse to provide for others and share (throwing a community BBQ, for instance, rather than just gorging alone). As for the sexual drive, an integrated masculinity doesn’t ask men to be celibate or ashamed of desire; instead, it promotes a view of sexuality as mutually fulfilling rather than one-sided. The phrasing sometimes used is to turn the urge to “fuck” into an urge to connect. Men can be taught that great sex isn’t about conquest or numbers, but about intimacy and respect – this way they still honour their libido, but in partnership with a willing equal, which ultimately can be more satisfying and ethical.

There is also a push to expand the acceptable emotional range for men. An empowered man in the 21st century might shed the old stoicism enough to be a present father, a loving husband, a supportive friend – roles that require patience, empathy, and sometimes vulnerability. None of these are incompatible with being strong or brave. In fact, it can take more courage for a veteran soldier to admit he has PTSD and needs help (breaking the stoic mold) than to say nothing. The integrated masculine ideal thus includes emotional courage. Movements like #MenToo or organizations like The Good Men Project emphasize storytelling where men discuss their feelings and struggles, aiming to reduce stigma. The logic is: if men feel internally balanced and emotionally supported, they are less likely to act out their frustrations in destructive ways. That means fewer random fights or rage-fuelled incidents – proof that allowing some “softness” can actually curb the negative expressions of “hard” masculinity.

Even in academia, some are reframing masculinity in positive terms. The concept of “positive masculinity” has been explored – identifying traits traditionally seen as masculine that can be beneficial. For example: protectiveness (when it means standing up for what’s right), leadership (when used to serve others, not just self), risk-taking (for noble causes, innovation, or defending the weak). These are elements of that primal male spirit employed for society’s benefit. One could argue that many of the world’s heroic acts – from firefighters rushing into burning buildings, to explorers venturing into unknown terrains, to activists bravely confronting injustice – draw on very masculine-coded virtues of risk and aggression, but guided by empathy or principle. An integrated masculinity encourages men to be heroes rather than tyrants, channelling the exact same inner forces.

Crucially, integrated masculinity also means men and women partnering rather than pitting against each other. Instead of viewing gender relations as a zero-sum (if men “win,” women “lose” and vice versa), a healthy model sees men’s and women’s liberation as tied together. Feminist author Gloria Steinem famously said, “Nobody wins when half the human race is losers.” Integrated masculinity accepts feminist insights – for instance, that consent in sex is non-negotiable, or that emotional openness is healthy – while still affirming that men can be proud of being men. In practical terms, this might look like a man who respects female colleagues and champions equality at work, yet also embraces his role as a father who will fiercely protect his children if needed, and a romantic partner who brings strength and tenderness to the relationship.

We can see signs of this evolving narrative in popular media too: the rise of the “emotionally intelligent action hero” (think of Marvel’s superheroes who often show vulnerability or moral conflict, not just machismo), or the popularity of athletes who are not only tough competitors but also outspoken about mental health (e.g., basketball players or male Olympic athletes openly discussing therapy and feelings). These role models combine toughness with sensitivity in a way that would have been rare decades ago. Even some military training programs now incorporate emotional resilience and empathy, recognizing that a soldier who can build community relations is as valuable as one who can shoot.

In conclusion, the core nature of men – the impulse to fight, feast, and mate – indeed remains part of the male psyche, but the path forward, as many see it, is neither to let these impulses run amok nor to futilely try to erase them. Instead, the challenge is integration: honouring the energy, ambition, and passion that come naturally to many men, while socializing men to apply those traits in constructive, respectful ways. As one commentator wrote, “masculinity is not a nihilistic pursuit of the appetites but a constructive use of man’s virtues for something higher.” In other words, men can still “fight” – but let it be fighting for justice or to protect loved ones, not bar fights or wars of aggression. Men can “feast” – in the sense of enjoying the fruits of their labour and celebrating life – without selfish excess or exploitation. Men can “fuck” – that is, embrace their sexuality – but as loving partners, not predatory players.

By synthesizing the lessons of history, biology, and modern egalitarian values, this integrated vision seeks to create a future where men no longer feel they must apologize for their nature, nor feel entitled to abuse it – rather, they can take pride in a masculinity that is both primal and elevated. Society, in turn, can benefit from the full, positive force of masculine energy – the daring, the strength, the drive – while minimizing its dangers. The manifesto of “Fight, Feast, Fuck” in defence of men, then, is not a call to return to the past unchecked, but a call to reclaim the best of masculinity: to recognize that these ancient impulses, when wisely guided, can contribute to a richer, safer, and more balanced human experience for everyone.

Sources:

- Evolutionary and cross-cultural research on male aggression and risk-taking en.wikipedia.org phys.org

- Studies on male vs female sex drive and mating behaviour medicalxpress.com dailyiowan.com

- Historical accounts of medieval masculinity, chivalry, and noble lifestyles genealogiesofmodernity.org battlemerchant.com

- Modern cultural observations on sports, masculinity, and mating displays dailyiowan.com dailyiowan.com

- Discussions of “toxic masculinity” and its impact on men’s psychology en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

- Perspectives of contemporary masculinity figures and critics (Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, etc.) facebook.com lens.monash.edu

- Feminist and sociological critiques of traditional masculinity and calls for change en.wikipedia.org lens.monash.edu

- Integrated masculinity viewpoints from psychological and social commentary en.wikipedia.org city-journal.org.

Thank You for Reading!

I hope you enjoyed this post and found it insightful. If you did, feel free to subscribe to receive updates about future posts via email, leave a comment below, or share it with your friends and followers. Your feedback and engagement mean a lot to me, and it helps keep this community growing.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into topics like this, don’t forget to check out the Donc Voila Quoi Podcast, where I discuss these ideas in more detail. You can also follow me on Pinterest @doncvoilaquoi and Instagram @jessielouisevernon, though my accounts have been shut down before (like my old @doncvoilaquoi on Instagram), so keep an eye out for updates.

Amazon has graciously invited me to take part in their Amazon Influencer Program. As such, I now have a storefront on Amazon. I warmly invite you to explore this carefully selected collection. Please be advised that some of my posts may include affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link and subsequently make a purchase, I may receive a modest commission at no additional cost to you. Utilizing these affiliate links helps to support my ongoing commitment to providing thoughtful and genuine content.

Comments (0)